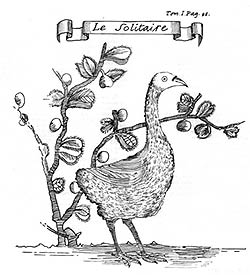

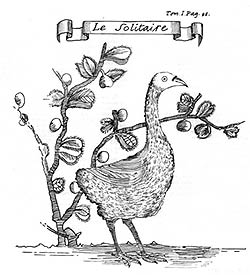

Solitaire of Rodrigues by

François Leguat (1692)

Solitaire of Rodrigues by

François Leguat (1692)

While the Dodo finally ended up on Mauritius, its cousin, the Solitaire, reached the tiny island of Rodrigues. The remoteness of Rodrigues sheltered the Solitaire from the rest of the world, and even today the island and the bird are almost unknown.

Only a few early visitors to Rodrigues recorded what the Solitaire looked like and how it behaved. Without these accounts we would know very little about it because soon after man started to inhabit the island, the Solitaire became extinct, leaving very little evidence that it ever lived there.

The first clue that there was a large bird living on Rodrigues came from Sir Thomas Herbert (1638) who mentioned in his Travels into Divers parts of Asia and Africa that the Dodo is 'generated here, and here only [meaning Mauritius], and in Dygarroys [Rodrigues]'.

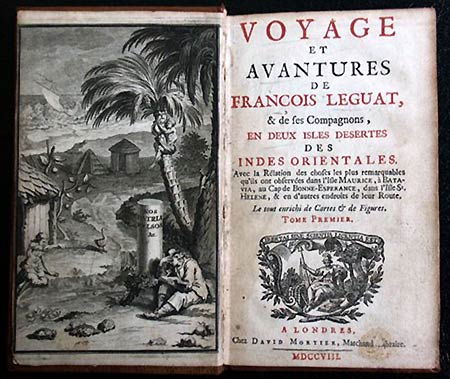

This Dodo-like, large bird, was first described by François Leguat de la Fougère (1708) who, together with his companions, lived on the island from 1691 to 1693. He wrote fondly of the birds and commented that they walked about 'with such pride and good grace that one cannot help but admire and like them, to the extent that quite often their good appearance has saved their lives.'

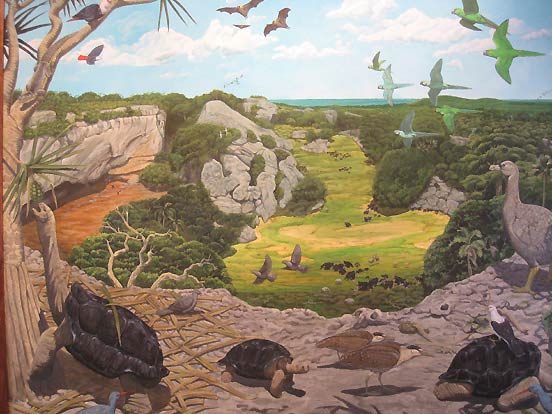

Rodrigues - Modern impression by Julian Hume

They were next described by a naval officer, Julien Tafforet, when he was marooned on Rodrigues in 1726 when he recalled that they could be seen 'strutting proudly about, either alone or in pairs, they preen their plumage or fur with their beak and keep themselves very clean.'

From these descriptions there is no doubt that the Solitaire was an elegant and striking bird, and perhaps more impressive than the Dodo of Mauritius.

After its extinction, the Solitaire failed to command the same interest as the Dodo for various reasons. To start with, the descriptions by Tafforet were wrongly filed and were lost until a Mauritian magistrate, F. J. J. Rouillard, accidentally found them in the Paris Ministére de la Marine in 1874. This meant that for a long time the descriptions of the Solitaire came from just one eyewitness.

The promotion of the Solitaire was not helped by the fact that many scientists cast doubt on the credibility of Leguat, and even those who accepted his accounts thought that it was the same bird as the Dodo in Mauritius. J. V. Thompson (1829), a surgeon and zoologist, who read Leguat's book, notes that 'we have in this last relation of Leguat, who resided amongst them for a considerable period, a detailed, although rude, description, and a natural history of the Dodo, probably the only one that was ever penned under such favourable circumstances.'

The editor of Thomson's work then adds that 'it is not likely that the three islands of the Mauritius group possessed each a distinct type of so singular and unique a bird.'

This failure to recognise the Dodo and the Solitaire as two separate species was completed when Georges Cuvier (1830), after receiving some Solitaire bones from Rodrigues, noted that they were found 'under a bed of lava, and in Mauritius'. This mistake was unforgivable, as no Dodo bones had been found in Mauritius at that time.

One of the aims of this Dodo site is to inform interested searchers about the natural history of the Solitaire, which found a small niche for a successful existence on Rodrigues for hundreds of thousands of years until it finally became extinct. It is hoped that an awareness of this bird, the island where it lived and its demise, will promote an understanding of the importance of conserving our environment and its dependent biodiversity. This in turn may help rescue Rodrigues from being one of the most environmentally degraded tropical islands in the world and turn it into a conservation success.